Penumbra | Gloom

Para llegar de San Miguel de Tucumán al Pozo de Vargas recorrí, por 15 minutos, un paisaje indiferente con olor a limón, donde la cotidianidad escondió, durante 20 años, una de las fosas comunes más grandes de América Latina. Verdulerías, kioscos, vallas con propaganda política, e incluso, los cientos de limoneros compatibilizaban con esa neutralidad del ambiente. Solo las fachadas grises de las casas parecían querer augurar algo de la pesadumbre oculta en lo profundo aquel lugar.

Una vez en el pozo el viaje no estaba completo, puesto que, para llegar al destino final había que descender 40 metros bajo el suelo, donde el olor a tierra húmeda no me revelaba estar en una tumba. La sensación térmica de frío y humedad me manifestaba estar en lo más puro de la naturaleza, donde nace agua cristalina y, en plena oscuridad, junto con la tierra negra, la virtud de la fertilidad.

To arrive from “Tucúman of San Miguel” to the “Pozo de Vargas” I toured for 15 minutes an indifferent landscape with lemon smell, where the daily life hid during 20 years, one of the largest mass graves in Latin America. Grocery stores, kiosks, billboards with political propaganda, and even, hundred of tree lemons compliant with that environmental neutrality. Just the gray facade houses looked like they want to augur something of the hid gloom in the deepest of that place.

Once you are on the well, the trip was not complete, being as, for arrive to the final destination you had to descend 40 meters under the ground, where the wet ground smells was not revealing me that i was in grave. The thermal sensation of the cold weather and humidity showed me to be in the purest part of the nature, where crystalline water borns, and, in the dark, close to the black ground, the virtue of fertility.

Sin embargo, lo aterrador no radicaba en el sitio per se, sino en el conocimiento de que fue la voluntad humana la que hizo de este un lugar de horror; en la conciencia de la violencia desbordada que sucedió y que fue contenida allí durante años, porque mientras desciendes y se va apagando la luz, y hueles la tierra, recuerdas que en este espacio agonizaron tantos, murieron tantos… Y se hace bastante explicito el macabro propósito de sus victimarios: que no los encontraran nunca.

Debido a su ubicación estratégica, el Pozo de Vargas, construido a fines del siglo XIX para abastecer de agua a las máquinas ferroviarias de vapor de la zona, fue utilizado por la última dictadura militar argentina (1975-1983) como sitio de inhumación clandestina. Posteriormente, su rastro fue borrado del paisaje y soterradas las pruebas de la barbarie.

However, the frightening was not about the place per se, but the knowledge that was the human will what made of this horror place; in the awareness of overflowing violence that happened and that was held there for years, because while you descend and thelight is turning off, and you smell the land, you remember that in this space agonize many people, die many people… And it becomes very explicit the macabre purpose of their victimizers; that never were found.

Due to its strategic location, the “Pozo de Vargas”, built in the late 19th century to supply water to steam railway machines in the area, it was used for the last Argentine military dictatorship (1975-1983) as a clandestine burial place. Subsequently, its trace was erased from the landscape and buried the evidences of the barbarism.

El camino al Pozo de Vargas fue trazado por las palabras. Fueron los relatos de los vecinos, de los habitantes del territorio que, venciendo un miedo instaurado en la comunidad a hablar, permitieron descubrir un suelo trastocado, una tierra que pertenecía a otra tierra, lo que fue el primer indicio de que habían encontrado la fosa común. Tras dos años de excavación, entre los 28 y hasta los 32 metros, se encontraron los primeros restos óseos. Bajar a la tiniebla, en este caso, no era solo una metáfora. Allí, donde hacer memoria es, literalmente, desenterrar, han trabajado incansablemente los arqueólogos del Colectivo de Arqueología, Memoria e Identidad de Tucumán (CAMIT) quienes, en un sólido compromiso con la verdad, han dedicado 20 años de sus vidas a escarbar.

The roud to the Pozo de Vargas was traced for by the words. It was the tales of the neighbours, of the resident’s territory that, overcoming a fear established in the community to speak, allowed to discover a disrupted ground, a land that belonged to another land, it was the first indication that they had found the common graves. After two years of excavation, between 28 meters to 32 meters, were found the first bones remains. Go down to the darkness, in this case, was not just a metaphor. There, where remembering is, literally, dig out, have worked tirelessly the archaeologists of the “Colectivo de Arqueologia Memoria e Identidad de Tucumán (CAMIT)”, who, in a solid commitment with the truth, have dedicated 20 years of their lifes to dig out.

Con todo, visitar el laboratorio forense me turbó en mayor medida que el descenso a la penumbra del pozo, puesto que en este espacio aséptico habitaban ya los restos rescatados, los huesos, las prendas, los lazos con que los amarraban, los vendajes con que les tapaban los ojos, las cintas transparentes de embalar cajas con que los amordazaban, cuyas marcas permitieron a los forenses identificar la fecha de desaparición. El laboratorio fue una cita a secas con la muerte, con los testimonios de esas muertes.

En el arte, la memoria se suele construir a partir de los relatos, de los objetos, de los gestos, de los afectos. Para la ciencia, esta búsqueda implica trabajar directamente con la memoria del cuerpo, el ADN. Significa acercarse al cuerpo expuesto, estar próximo a lo más profundo de lo que somos, a nuestros huesos. A su vez, todo lo que hallan los arqueólogos son tesoros que permiten rastrear las huellas de identidad que reposan en un fragmento de lo que, una vez, fue una persona. Definitivamente, en algún momento los muertos reclaman su espacio y salen a la luz.

With all, visit the forense laboratory disturbed me even more that the descent into the gloom of the pit, because in this aseptic space already inhabited the rescued remains, the bones, the clothes, the ties with they were tied, the bandages they were blindfolded with, the transparent tapes of packing boxes with which they were gagged, marks that allowed to the forenses identify the disappearance date. The laboratory was a dry date with the death, with the testimony of these deaths.

In the art, the memory is usually built on the basis of stories, of the objects, of the gestures, of the affections. For the science, this search involves working directly with the body's memory, the DNA. It means approaching to the exposed body, to be close to the deepest of who we are, to our bones. In fact, all that archaeologists find are treasures that make it possible to trace the footprints of identity that rest in a fragment that, once, was a person.

Definitely, at some point the dead claim their space and come to light.

No obstante, estas imágenes crudas de la muerte, si bien ofrecen información de la identidad del desaparecido y permiten reconstruir la verdad de su suplicio, no representan por sí mismas al ser amado. Son la transición del ser que estaba oculto al que aparece. Pero el encuentro con estos restos fragmentados tampoco permite la elaboración del duelo en su sentido pleno, puesto que, tras la ansiedad de la búsqueda, los rituales de entierro no son posibles sobre un cuerpo incompleto. Así fue como escuché el relato de una mujer que se reúsa a enterrar lo que han encontrado de su hermano, puesto que “él era una persona completa y no unos pedazos de huesos”. Incluso, gran parte de los familiares de estas personas siguen en el umbral y se niegan a donar sangre para identificar a sus muertos.

Nonetheless, these crude images of death, although they provide information on the identity of the missing person and make it possible to reconstruct the truth of their ordeal, do not represent by themselves to the loved person. They are the transition of the person that was hidden to the one that appears. But the encounter with these fragmented remains also does not allow the elaboration of mourning in its fullest sense, in as much as, after the anxiety of the search, burial rituals are not possible with an incomplete body. So that was I heard the story of a woman that refuse to bury what she had found of her brother, being as "he was a whole person and not just a few pieces of bones". Even, the biggest part of the members family of these persons are still in the threshold and they deny to donate blood for identify their death.

A lo largo de mi obra he trabajado el concepto de dolientes, para comprender a las víctimas del conflicto a partir de la universalidad del dolor, es decir, del que se duele por el otro y del que se duele a sí mismo. No obstante, en conversaciones con los familiares de los desaparecidos del Pozo de Vargas, pude comprender que ellos no se consideran a sí mismos como víctimas, sino como querellantes, porque están, constantemente, en búsqueda de justicia. En este sentido, su trabajo no se centra en la elaboración del duelo, sino en el reclamo por la verdad. Al respecto, una querellante me decía: “Yo no quiero salir ni entrar al duelo de mi papa, quiero justicia”, y esto me hizo valorar enormemente el nivel de dignidad con que estas personas exigen sus derechos, sin conformismo, resignación o tolerancia frente a respuestas aparentes o superficiales. En este aspecto, Colombia ha tenido mucho que aprender de Argentina, en términos de organización social y de la exigencia de la verdad.

Throughout my work I have worked on the concept of mourners, to understand the victims of the conflict from the universality of pain, I meant, of the one who hurts for the other and the one who hurts himself. However, in conversations with the family members of the missing persons of the Pozo de Vargas, I could understand that they don’t consider themselves as a victims, but like complainants, because they are, constantly, searching the justice. In that sense, the work is not focus in the grief processing, but in the claim for the truth. About this a complainant told me: “I don’t want come out nor come in to the mourning of my father, I want justice” and this make me appreciate hugely the dignity level with those persons demand their rights, without conformism, resignation or tolerance facing to aparent or superficial answers. In this aspect, Colombia has had a lot to learn from Argentina, in terms of social organization and the demand for truth.

Por otro lado, también tuve la oportunidad de visitar diversos hogares de los desaparecidos. Una de dichas experiencias fue la de encontrarme con una familia que se reunía por primera vez después de la pandemia. Esto me permitió presenciar la conversación y ver como la memoria del padre, del esposo se construía entre todos, a partir de la puesta en común del relato individual: “yo alcancé a ver el carro que se lo llevó…”; “mi viejo olía a madera, porque se dedicaba a fabricar ataúdes” … Comprendí que era la primera vez que hablaban, todos juntos, de este tema. Estar presente en ese momento e identificar esa necesidad de escucha de la familia me permitió reconocer que, a pesar de lo que nos falta por recorrer y aprender en Colombia, sí considero que hemos logrado avanzar cierto recorrido en relación con el trabajo psicosocial en el marco del conflicto armado, comprendiendo la necesidad del tejido social en la elaboración del duelo.

By other side, also I had the chance to visit different missing person’s homes. One of those experiences was about meet a family that joined for the first time after the pandemic. This allowed me to witness the conversation and see how the father's tale, of the husband were built all together, from the sharing of individual stories: “I could see the car that caught him”… “My old man smelled to Wood, because he was dedicated to make coffins his work was to making coffins… I understood that it was the first time that they spoke, all together, about that subject. To be present in that moment and identify that need to listen of the family allowed me to recognize that, despite we have to tour and learn in Colombia, I do consider that we have achieved to move forward some route in relation with the psychosocial work in the context of the armed conflict, understanding the need of the social fabric in the elaboration of mourning.

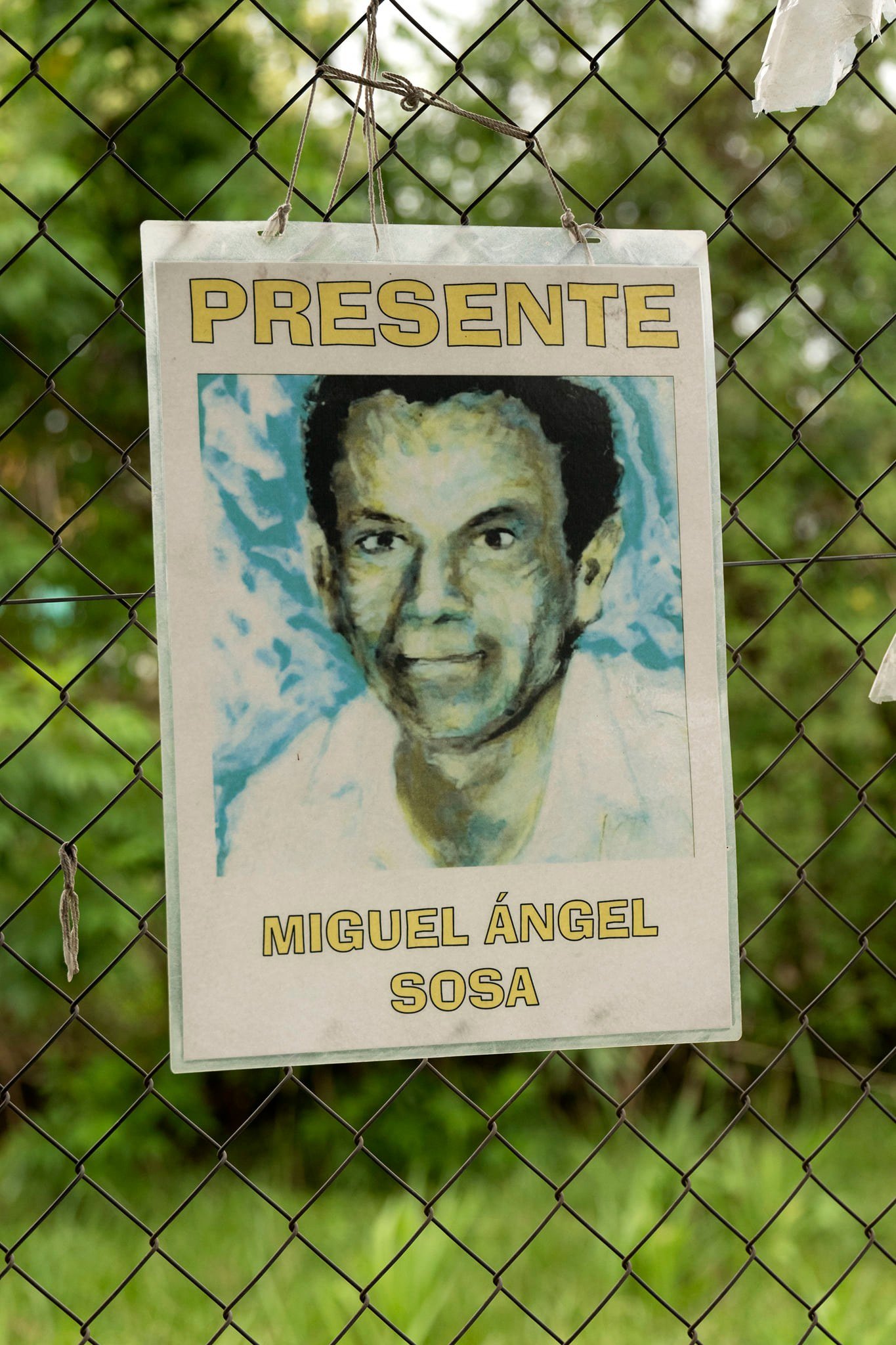

Y es que es ese duelo, que nos atraviesa como sociedad, lo que nos posibilita habitar los relatos, las palabras de los otros, y lograr construir imágenes que nos permitan representar a nuestros ausentes y a nosotros mismos. Un mantel bordado por una mujer, los letreros de búsqueda que se sacan a una marcha no representan tan solo al desaparecido, encarnan también al querellante, al doliente, a las familias, a tantos años de búsqueda.

Después de que bajé al pozo, a esa oscuridad donde no se veía nada, pero donde lo hubo todo, una mujer, bióloga, querellante, pero también una doliente, me preguntó: “¿cómo es?, ¿a qué huele? Ella nunca se había animado a bajar a este lugar con tal significación de horror. Yo le respondí que olía a tierra mojada, a limpio. Más adelante ella quiso bajar y, con su mirada de bióloga y su amor por la naturaleza, pudo transformar su sentir del pozo, comprendiéndolo desde su sentido más elemental, como un lugar de donde mana el agua.

And because is that mourning, that crosses us as a society, what make us possible live the stories, the other’s words, and achieve to build images that allow to represent to our missing persons and also to ourselves. A table cloth embroidered by a woman, the search signs that are taken out at a march do not represent only the missing person, they also embody the complainant, the mourner, the families, so many years of searching.

After I went down to the well, with that darkness where I couldn’t see anything, but where it was everything, a woman, a biologist, a complainant, but also a mourner, asked me: “How is it?”, “What does it smell to?” She had never encourage to go down to this place with such significance of horror. I answered her that it smells to wet ground, clean. Later she wanted to go down and, and with her biologist look and her love for the nature, she could convert her feel of the well, understanding from her most elemental sense, as a place where the water borns.

Fui invitada allí por Andrés Romano para asesorar y proponer un proyecto de memoria que se trabaje a partir de las prendas y los objetos rescatados; y espero haber contribuido desde mi quehacer y saberes en este proceso. Pero, adicionalmente, este encuentro permitió articular propuestas y la proyección de círculos de trabajo psicosocial, que se trabajarán en intercambios entre los dos países, y que, más adelante, verán también su fruto en El Oratorio, que es una obra en proceso.

Mis agradecimientos especiales a los artistas Darío Albornoz y Marcela Alonso por toda su generosidad; y a quienes han pasado, y pasarán, años bajo la tierra, para exhumar identidades, memorias vivas y verdades que dignifican:

I was invited thete for Andrés Romano to advise and propose a memory Project that was worked from of the clothes and the rescued objects; and I hope have contributed from my chores and knowledge in this process. But, in addition, this meeting made it possible to articulate proposals and the projection of psycho-social work circles, that will be worked in exchanges between the two countries, and, that, later, also will see bear fruit in “El Oratorio”, that is a work in process.

My special gratitude to the artists artistas Darío Albornoz and Marcela Alonso for all their generosity; and to who have passed, and will pass, years under the ground for exhuming identities, living memories and truths that dignify:

Los arqueólogos / The archaeologists

Andrés Romano

Divino boja

Marisa López Campeny,

Aldo Geronimo,

Víctor Ataliva

Ruy Zurita

*

A Emma y Tiago gracias por su alegría / To Emma and Tiago thanks for their joy.

***